Sermon for the Seventeenth Sunday after Pentecost

If I were to ask you, “What’s the opposite of a wise person,” it’s quite likely that you’d say, “a foolish person.” In support of that answer, you could refer to the parable that Jesus told about 10 bridesmaids for a wedding. Five of them brought extra oil for their lamps, and five didn’t. The wedding was delayed well into the night because the bridegroom hadn’t come yet, and when he arrived, five of them were out of oil and their lamps were going out. That’s often called the parable of the wise and foolish virgins, or wise and foolish bridesmaids.

That would illustrate your answer pretty well. Being wise means knowing important things and being able to reason well about matters, while being foolish means either just not being very bright or being too lazy or careless to learn.

“Foolishness = the opposite of wisdom” is the usual idea. But the way James speaks about wisdom — and its opposite in our text — goes deeper. Here, being wise, having wisdom, is not just a matter of knowing things, but also of ethics, or of dealing in the right way with other people. Therefore, the true wisdom, that which is “from above” — that which is, from God — is peaceable and honest, and “willing to yield.” True wisdom respects the needs and concerns of others.

And its opposite? James doesn’t call the kind of thinking that leads to “envy and selfish ambition” foolishness but, in verse 15 of this chapter, he says that it’s a distorted wisdom — that is “earthly, unspiritual, devilish.” It comes from below, being the opposite of the wisdom that comes down from above.

Throughout the letter of James, we hear that emphasis on thinking and acting in the right way, especially in relationships with other people. The letter is about Christian ethics, not Christian doctrine. (This is third use of the law.)

Probably the verse from James that’s quoted most often is, “So faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead.” Jesus is mentioned by name only twice, and nothing is said about his cross and resurrection. These features have led some scholars to argue that this was originally a Jewish text that a Jewish Christian writer then made use of, The wisdom from above.

For all the good behavior that is emphasized here, we’re missing something important if we see nothing but that. At the beginning of the letter, we’re issued an invitation: “If any of you is lacking in wisdom, ask God, who gives to all generously and ungrudgingly, and it will be given you.” And now, in our text in the middle of the letter, we’re focusing on wisdom — what it isn’t and what it is. The true wisdom is that which “comes down from above.” Considering the invitation that I just quoted, that clearly means, “from God.” And that God given wisdom is what works through our gift of faith to produce good works.

Language about “coming down from above” might make us think of a guru, a spiritual master or religious teacher, who goes to a mountain top to receive inspired teaching, and then brings it down to us. The figure of Moses comes to mind. But that’s already been done! Moses went up Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments and other laws for Israel well over a thousand years before James was written. Just those ten commandments are already a good source of wisdom. Are they not a wise guide to proper thinking and action? But the wise people of Israel weren’t content with just repeating those laws. They reflected on them and sought their fuller meaning. They did this to the point that they made the Law into works righteousness. (Did they – Do we?)

There’s a good deal about wisdom in the Hebrew scriptures, where we find the saying, “The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom” repeated (with some variations) several times. This emphasis is especially strong in the book of Proverbs, where wisdom is personified as “Lady Wisdom.”

In chapter 8, she tells of how the Lord created her before the world began, and how she was with God as the heavens and the earth were made. Then Wisdom appeals to people to become wise and concludes with both a promise and a warning.

For whoever finds me finds life and obtains favor from the LORD;

but those who miss me injure themselves;

all who hate me love death.

That means that the early Christians had a strong “wisdom tradition” behind them. In Luke’s gospel, we’re told that as a boy, Jesus was “filled with wisdom” and “increased in wisdom,” and there are allusions to that personified figure of Wisdom from Proverbs.

It sounds as if Jesus himself is being thought of as wisdom. Paul makes that explicit in First Corinthians when he says that “Christ Jesus … became for us wisdom from God, and righteousness and sanctification and redemption.”

The meaning is pretty clear. Jesus Christ reveals in his own person the wisdom that comes down from above.

What would Wisdom do?

So while James doesn’t say much about Jesus by name, it’s not a stretch to think that the emphasis on the wisdom from above points to Jesus.

When our text speaks of that wisdom as being “full of mercy and good fruits,” we’re reminded of the way in which Peter summed up Jesus’ ministry when he spoke to the first gentile converts to the faith: “He went about doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil.9

We could spend a lot of time fleshing out that brief statement with all the stories that the gospels tell about the ways in which Jesus dealt with people in need.

Jesus proclaimed the love of God and God’s coming reign to the poor, he healed those who were sick physically or mentally, he provided food for those in need, and freely forgave the sins of people.

Sometimes he did those things in response to requests from people who were suffering, and sometimes he just saw what was needed and did it. And our text, in encouraging us to live wisely, points us to the same kind of life.

Of course, Jesus sometimes pointed to failings in people’s lives and called them to change. His ministry began with a call to repentance, and our text, which criticizes false “wisdom,” does the same. But pointing out errors and inviting change differs from simple condemnation.

It’s not quite as popular today, but a few years ago the phrase “What would Jesus Do?” was often used by some Christians. You could get wrist bands with acronyms of that phrase, WWJD. The idea was what Jesus would do in some situation should be a guide for what we do.

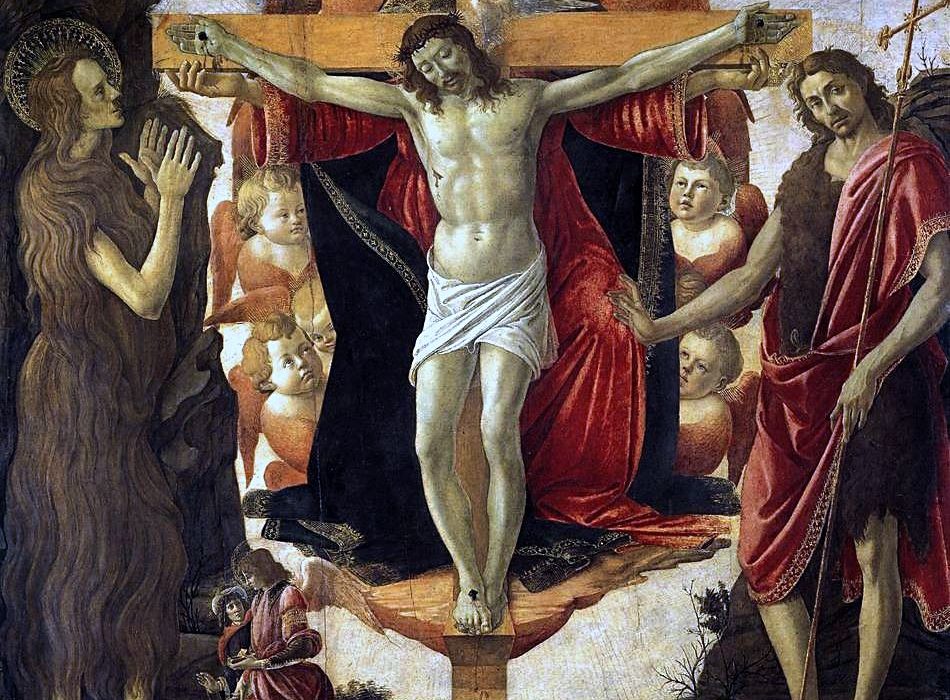

Sometimes what Jesus would do will be obvious, and in other situations in today’s world it might be hard to know how he would respond. But we know in a very basic sense what Jesus would do. He would die for us. His blood would justify us through the forgives of our sins.

Jesus’ supreme act of love for us was his death on the cross and his resurrection to reconcile us to God. This is that beautiful gift of Wisdom from on high. Or as St. Paul says, it is the supreme display of God’s wisdom: “Christ, the power of God and the wisdom of God.” So to sum up James, let’s just say, “The one who is the Wisdom from on high invites us to take up the cross and follow him. This is the faith that enables our good.” Amen.

Preached by Pastor Pfaff

Sermon Text: James 3:13 – 4:10.