Sermon for the Last Sunday of the Church Year

‘Blessed are the barren and the wombs that never bore and the breasts that never nursed.’

+INJ+

Blessed indeed. Who would bring a child into

this world.

I do not mean to speak of this time or this period or any particular child.

Neither does the Lord. I do not wish to say that we live in some peculiar

moment where having a child is a miserable thing. Neither does the Lord.

For in the Garden, the Lord already spoke: ‘In pain shall you bear

children.’

Many simply think this refers to labor, which, from what I gather, is

painful. But this pain is but a symbol of the true suffering of giving birth;

that you give birth to a child, a child shackled by sin, a child that will one

day die.

This is the pain.

It is the curse of man that he shall work all the days of his life just to

feed a family, so they do not starve and pass away. It is the curse of

woman that she shall labor all of her days for that which will pass away,

that is, her children.

For it is written: ‘You shall surely die.’

No one wishes to see their child die, and most will not; rather, their

children will watch them die. This is no comforting thing. For a child mourns

for their parents as much and a parent mourns for their child. This is the

world of things that pass, of things that die; where one thing overcomes

another; where one thing prevails upon another; this is the world we

chose.

Therefore, the God whom we betrayed in the garden does not say anything dark

and controversial. He only repeats the logical wisdom of the fate which we

brought upon ourselves in our Original Sin: ‘Blessed are the barren.’

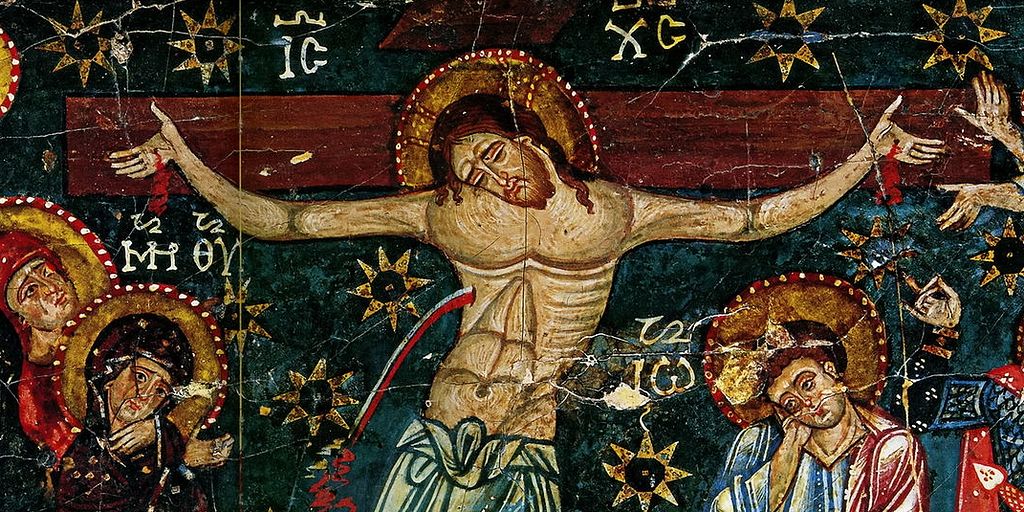

In our reading, Our Lord Jesus is crucified, the

death of traitors, and indeed our Lord is a traitor, for being made man He is a

traitor to this world made by men. He is a stranger in the hell we made, and

because He did not call our hell a heaven, we put Him to death.

A man crucified with Him cries out, ‘are you not the Christ? Save yourself

and us!’ Perhaps this man was being sarcastic, an ancient trait of angry

men. But is this not the prayer of the Church? What does Lord have mercy mean

but ‘save yourself and us?’ For indeed the Lord will be saved by His

resurrection, and the path of salvation is laid down for us in His Ascension.

Yet another sinner cries out: ‘Jesus, remember me in your kingdom.’

Though these seem to be portrayed as contradicting one another, one is

just the answer to the last. ‘Save us.’ ‘Remember us.’

We speak of the crucifixion, a day of violence and of gore; of blood, and

of water. These things the Lord shed, having been made flesh for us, that we

might be saved, that we might be remembered.

We often say in Church that you should cross yourself to remember your

baptism. Yet we should know that in our remembering our baptism, God first

remembers us, even as He remembers His promise to not wipe out all life upon

the earth when seeing the rainbow He set in the clouds after the Great

Flood. God remembers His promises.

A mortal child is born, and at the moment of his birth he is destined to die.

This is the fate of all men. And because of this, all women ‘bear children

in pain,’ and the Lord says, ‘blessed are the breasts that never

nursed.’

Yet, the Lord bleeds, the Lord suffers. The Christ is on the cross. And His

side is pierced by a lance. Blood and water flow from the wound. Blood for the

chalice; water for the font. Christ says many things. Did He not also say ‘I

make all things new’?

What is born mortal is made immortal. What is born frail is made

invincible. And all this, by the water, and by the blood of the God who became

man, that we might become God.

As the water is poured upon a wretched sinner,

the Lord says only, ‘This shall be mine, on the day when I take up my

treasured possession.’

And on the day of death, what shall that water speak?

‘Today, you will be with me in paradise.’

+INJ+

Preached by Pastor Fields

Sermon Texts: Malachi 3:13-18; Colossians

1:13-20; Luke 23:27-43.